The global health landscape is facing unprecedented uncertainty, particularly in external funding. As donor priorities shift and funding landscapes evolve, it’s crucial for countries to reassess their health financing strategies and build resilient systems. For several decades, external funding and assistance have played a critical role in financing lifesaving health interventions across Africa, (and other distressed countries in the developing world) helping to avert millions of deaths. Since 1990, such support has contributed to a 50% reduction in under-five mortality, largely by improving access to vaccines and expanding immunization coverage. Additionally, foreign aid through initiatives like PEPFAR currently supports 20 million people living with HIV—including over 500,000 children in 55 countries, most of them in Africa—to receive life-saving antiretroviral treatment.1

However, recent shifts in the global health financing landscape threaten to reverse these gains. The United States Government’s recent decision to withdraw from the World Health Organization, along with executive orders to review foreign aid spending will potentially reshape global health financing. As the world’s leading donor, any significant reduction in U.S. external aid certainly will send shockwaves throughout the global health ecosystem.

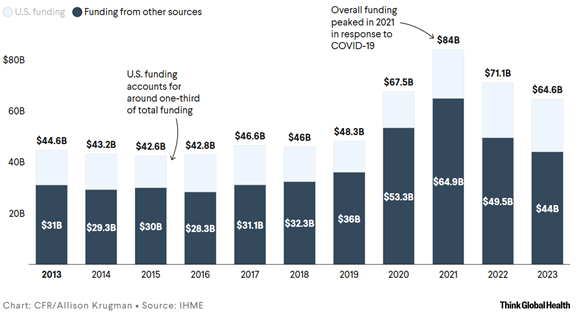

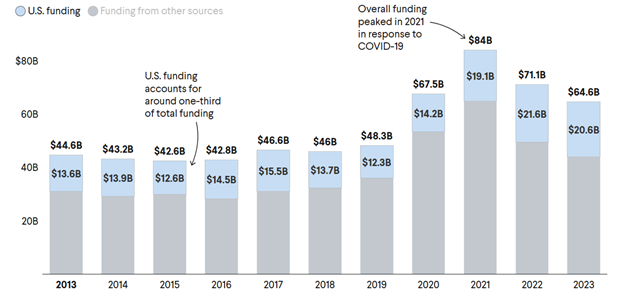

It is important to note, however, that development assistance for global health was already on the decline even before the United States’ executive orders. In recent years, official development aid to Africa has gradually decreased. Globally, health funding dropped from around $84 billion in 2021—driven largely by the COVID-19 response—to about $66.4 billion in 2023, only slightly above pre-pandemic levels. During the same period, while U.S. funding remained relatively stable, contributions from other countries fell sharply from $64.9 billion in 2021 to $44 billion in 2023 (See figures 1 and 2).1

The decline in external funding is expected to create significant gaps in health financing, placing already fragile health systems under immense strain. This financial downturn comes at a time when disease outbreaks are on the rise. Since 2022, the Africa CDC has recorded a 40% increase in public health emergencies on the continent.2

Figure 1 Total global health funding and funding from other countries except the United States from 2013 – 2023.3

Figure 2 Total global health funding against funding from the United States from 2013 – 2023.3

Within the same period, two Public Health Emergencies of International Concern (PHEICs) have been declared—both linked to the high transmission of Mpox. The recent emergence of Marburg virus in East and Central Africa is raising concerns about the resurgence of viral hemorrhagic fevers. Africa’s dependence on imported medical products such as drugs.2 Diagnostics and vaccines, is another major cause for concern. For instance, Africa manufactures less than 1% of the global vaccine stockpile yet consumes 12% of global vaccines. Consumerism tendency of Africa without a basis for capacity to pay is a dangerous state which we must begin to redress.

Although the full extent of how disruptions to external funding will impact health systems remains uncertain, reductions in support for HIV programmes are expected to have devastating consequences, if left unaddressed. UNAIDS estimates that if PEPFAR were halted, an additional 6.3 million AIDS-related deaths could occur.1

Zambia, like many other countries, would experience a seismic shock to its health system if external funding were to decline significantly. The country remains heavily dependent on donor support. In 2022, both the Zambian government and external donors each accounted for 41.4% of total health expenditure. The remaining funding came from social health insurance (6.3%), out-of-pocket payments (9.7%), private health insurance (0.1%), and other NGO sources (1.1%).3

An opportunity to rethink health financing:

While the prospect of declining external support may seem daunting, it also presents an opportunity to rethink how we finance health and sustain public health security. Rather than viewing this as a setback, we can use it as a catalyst to build more resilient and sustainable health financing. To attain this, we must think of the adjustments needed to turn what only appears as a challenge into an opportunity. The following are key actions we can consider as we move a new path forward:

1 Leverage global and regional collaborations:

We must embrace multilateralism and partnerships, especially in the face of rising unilateral decision-making. Infectious diseases do not recognize national borders, and their health and economic impacts often spill over into neighbouring countries and regions. This makes cross-country collaboration and strong multilateral engagement not just beneficial, but essential. During the COVID-19 pandemic, multilateral agreements on vaccine access were instrumental in mitigating global disparities.4 One such forward-looking initiative is the proposed WHO Pandemic Agreement, which seeks to strengthen global preparedness and response to future pandemics of similar magnitude. The Pandemic Agreement will also prioritise sharing of information between countries including genomic sequencing of pathogen.4 Similarly, the Africa CDC is championing the establishment of the Africa Epidemics Fund—a pooled resource to support emergency preparedness and rapid response. It is also proposing innovative mechanisms such as regional solidarity levies, including an airline tax, to mobilize additional funding.2 Countries across the continent should rally behind such initiatives; and indeed, pick up cues and domesticate some of the practical options. For example, a $50 additional levy of flights could result in $50 million when a million persons fly.

2. Prioritise high impact, evidence informed interventions:

Now more than ever, it is crucial that public health spending is guided by the best available evidence. This entails building local expertise in health financing to inform resource allocation and support difficult trade-off decisions when resources are limited. It also calls for strengthening—and, where necessary, establishing—health economics, research, and policy units that can bridge the gap between evidence and policymaking.5 This should transcend across all levels. At point of implementation, officers should ensure programmes undertaken represent value to all stakeholders. This for Zambia must include reduction of unnecessary “workshop meetings”, reduction of travel to only essential trips.

3. Exploring new and innovative financing models:

It is abundantly clear that countries must increasingly tap into domestic resources to sustain and advance public health security, particularly in the wake of a steep decline in external support. Strengthening domestic commitment is vital to protect health systems from the unpredictability of international funding. While increasing government health expenditure is necessary, bridging the full gap left by diminishing donor support may not be immediately feasible. Government’s commitment to serving external debt and other competing social services and programmes make this increasingly unlikely. Nonetheless, a country like Zambia whose fiscal imperatives are presently being re-aligned and gaining unprecedented traction with a promise of real economic gains, there are opportunities. Could a proportion of the Constituency Development Fund be considered specifically to support health care for the elderly and poor? Can manufacturers of non-degradable waste such as plastic bottles and carry bags the clog the drainages causing strain on the sanitation be levied to contribute to control of resultant waterborne diseases? More direct levies on tobacco and alcoholic beverages could contribute to infrastructure and commodities for care of cancer and other chronic diseases. And indeed, gains expected from revamping the copper production, and we are on our way towards the target 3 million metric tons a year, could already be structured with a direct feed into health care.

In fact, according to the World Health Organization, debt remains a major constraint on healthcare spending in many countries.4 Thus, as Zambia works her way out of unsustainable debt through the restructured program, opportunities exist for health care improvement. Indeed, we must also shift our attention to new and innovative financing models, such as public-private partnerships and collaborations with philanthropic organizations. The goal should be to leverage the private sector’s comparative advantages while attracting long-term investment in infrastructure development, local vaccine manufacturing, digital health, and enhanced logistics systems.

Let’s work together to build a more sustainable and equitable health financing system, ensuring that everyone has access to quality healthcare, regardless of their circumstances.

References

- Krugman, A. (2025) A “Defining Moment” for Global Health Funding. Think Global Health. Available at: https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/defining-moment-global-health-funding (Accessed: 2 May 2025).

- Africa CDC. (2025) Africa’s plan to fill health funding gaps amidst declining coffers. Available at: https://africacdc.org/news-item/africas-plan-to-fill-health-funding-gaps-amidst-declining-coffers/ (Accessed: 2 May 2025).

- Human Rights Watch. (2025) New data exposes global healthcare funding inequalities: World Health Day a clarion call to improve public health funding. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/04/10/new-data-exposes-global-healthcare-funding-inequalities (Accessed: 2 May 2025)

- Ammar, W., Baggoley, C., Harvey, F., Haque, Y.A., Konyndyk, J., Jee, Y., Sow, S., Sy, E.A. and Tam, T., 2025. Finalising the WHO Pandemic Agreement for a safer future. The Lancet, 405(10487), pp.1339-1340.

- Clinton Health Access Initiative (2025) Building local health financing expertise. Available at: https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/research/local-health-workforce-global-health-funding-collapses/ (Accessed: 2 May 2025)

.